Introduction

In modern security — whether public or private, armed or corporate — risk analysis has evolved from a theoretical discipline into a critical operational necessity. Every organization that protects assets, people, or infrastructure must understand one central truth: risk never disappears; it can only be measured, managed, and mitigated.

For security professionals, this is more than an abstract exercise. It determines how quickly they can react, how effectively they can allocate resources, and how confidently they can defend their actions under legal or tactical scrutiny. The purpose of risk analysis is not merely to identify what could go wrong, but to anticipate how, when, and why it might happen — and to prepare accordingly.

The Meaning of Risk in Security Operations

The International Organization for Standardization defines risk as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ISO 31000:2018). In security terms, uncertainty often takes human form: a criminal, a protester, or a hostile insider. Risk analysis, therefore, is an effort to translate unpredictability into something measurable.

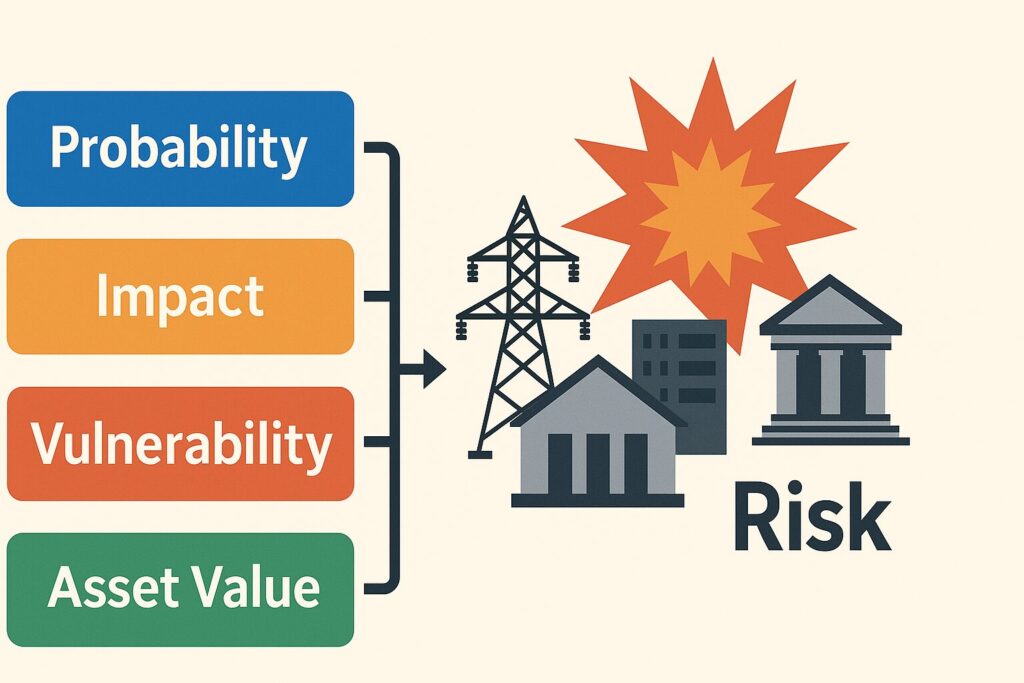

In essence, risk is a function of probability, impact, vulnerability, and asset value. A low-probability event can still be catastrophic if its consequences are severe enough — as seen in recent attacks on energy grids, data centers, and public facilities. Understanding this dynamic allows commanders and analysts to move from reactive posture to preventive control.

Why Structured Risk Analysis Matters

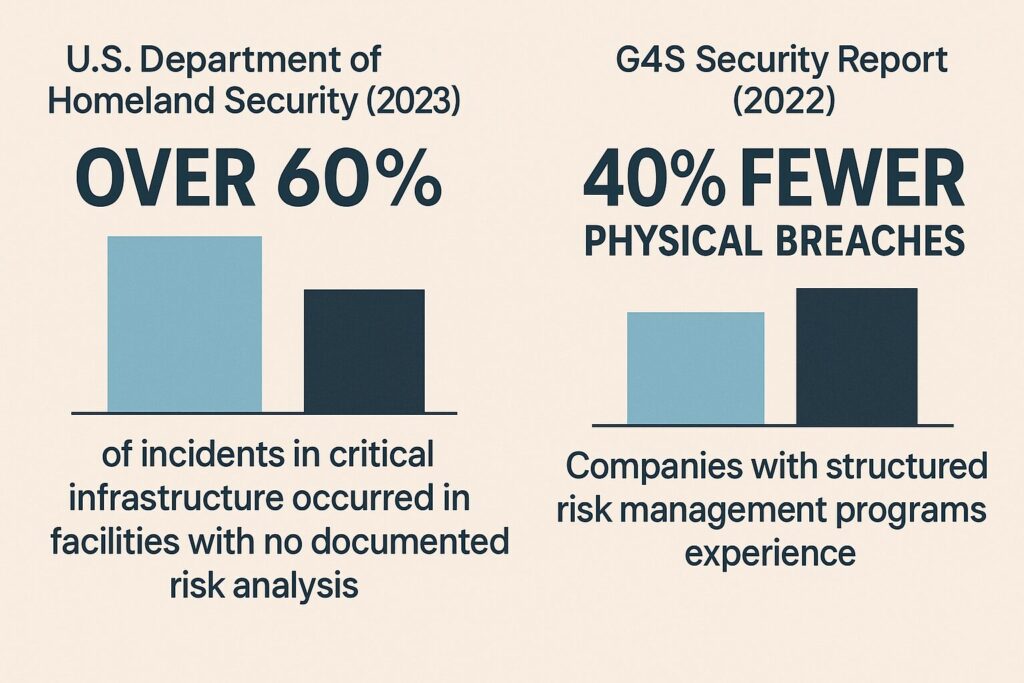

Organizations that skip formal risk assessment often fall into the same trap: they prepare for yesterday’s threats instead of tomorrow’s. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2023) found that over 60% of incidents in critical infrastructure occurred in facilities with no documented risk analysis. Similarly, a G4S Security report (2022) revealed that companies with structured risk management programs experience 40% fewer physical breaches.

Risk analysis is not bureaucracy — it’s foresight quantified. It enables leaders to justify decisions, secure funding, and demonstrate due diligence in court if necessary. In a world where negligence can be criminalized, being able to prove that you foresaw the danger is almost as important as preventing it.

Building the Foundation: How Risk Analysis Works

The process of analyzing risk begins with a clear understanding of what is being protected. Analysts start by defining the operational context: the site, the mission, and the surrounding environment. A power plant in a politically unstable region faces a different risk spectrum than a private academy or a logistics hub.

Next comes asset identification and valuation. Assets include not only tangible objects like vehicles, firearms, or facilities, but also intangible values such as information, brand reputation, and the trust of clients or citizens. According to NIST (2012), each asset should receive a “criticality score” — a numerical representation of how damaging its loss would be.

Once assets are mapped, the analyst moves to threat identification. Threats can be natural (floods, storms), accidental (equipment failure, negligence), or intentional (theft, sabotage, terrorism). Each must be paired with its corresponding vulnerability — the weakness that would allow it to succeed. A camera that’s offline, a guard distracted, or a single point of failure in an access system can all transform a manageable threat into a major incident.

From Uncertainty to Measurement

At the heart of any risk analysis lies the question: how likely is this to happen, and what would it cost if it did? To answer it, analysts use three main approaches — qualitative, quantitative, and hybrid.

Qualitative analysis relies on expert judgment to rate each risk as low, medium, or high. It’s simple, visual, and ideal when hard data is scarce. Quantitative analysis, on the other hand, assigns numeric probabilities and financial impacts, allowing for precise calculations and simulations. Hybrid models blend both — and are the most common in the field. A 2022 survey by the Center for Internet Security found that 71% of organizations rely on this combined approach, balancing practicality with accuracy.

Regardless of method, the goal remains constant: to transform complexity into clarity, giving decision-makers an evidence-based hierarchy of priorities.

Visualizing Risk: Models and Tools

Several visualization techniques help bring the invisible world of risk into focus. The Bow-Tie model illustrates the cause-and-effect chain of an incident: threats on one side, consequences on the other, and preventive controls in between. This format helps teams understand where to reinforce barriers.

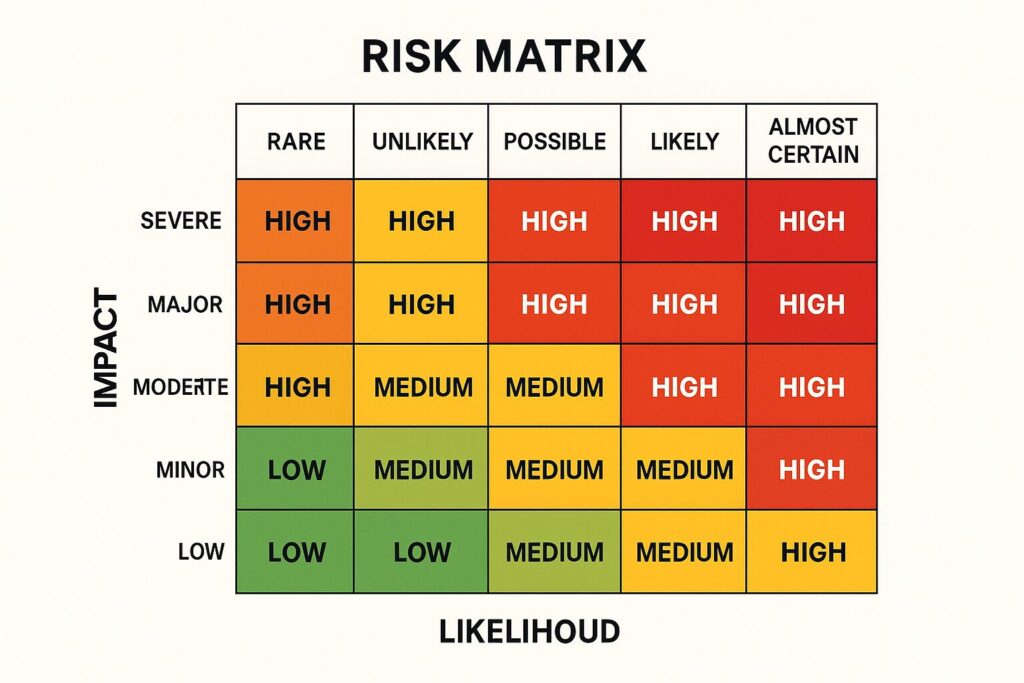

Similarly, the risk matrix — plotting likelihood against impact — remains one of the most widely used tools in security management. According to an ASIS International survey (2021), over 85% of corporate and governmental security directors employ some form of matrix in their daily decision-making. The reason is simple: it turns complex data into immediate action.

Turning Analysis into Action

Identifying risk is not enough; it must lead to risk treatment. Analysts typically choose among four strategies:

- Avoidance – eliminating the exposure entirely.

- Reduction – adding controls or improving training.

- Transfer – sharing risk through insurance or outsourcing.

- Acceptance – acknowledging low-priority risks and monitoring them.

Each decision must be documented. Accepting a risk is not negligence if it’s justified and recorded; ignoring it without evaluation is.

Continuous Monitoring and Adaptive Thinking

A risk analysis is not a static report. The ISO 31000 framework requires periodic reviews — ideally after every major incident, environmental change, or annually at minimum. Continuous monitoring ensures that what was once an acceptable risk doesn’t silently evolve into a critical one.

For armed professionals, this also means training adaptation. As threats evolve — from conventional assaults to drone reconnaissance or cyber-physical sabotage — the organization’s drills, standard operating procedures, and reaction times must evolve too. A modern security system is alive; it learns as much from what didn’t happen as from what did.

Major Methodologies and Frameworks

Globally, several frameworks dominate the field of operational risk management. The former NIST SP 800-30 (United States, now achived) provides a structured, government-tested methodology that can be adapted to physical security. The ISO 31000 (International Organization for Standardization) offers flexible guidance suitable for both small firms and large agencies.

Other structured methods include the CCTA Risk Analysis and Management Method (CRAMM) developed in the United Kingdom, the MEHARI system from France, and the EBIOS method, which focuses on identifying security objectives before selecting controls. Each of these frameworks shares a single goal: to bring consistency and comparability to a discipline often dominated by intuition.

Adversarial and Bayesian Thinking

In armed environments, risk is not static — it reacts. This is where Adversarial Risk Analysis (ARA) becomes relevant. Pioneered by Rios and Insua (2020), ARA treats the opponent as an intelligent decision-maker whose behavior changes in response to your defenses.

When applied to policing, military, or private security, ARA helps analysts predict how attackers might shift tactics once a vulnerability is closed. Combined with Bayesian models, which continuously update probabilities as new intelligence arrives, this approach allows for dynamic, real-time adaptation. It’s not just risk management; it’s strategic foresight in motion.

Adversarial Risk Analysis (ARA)

Adversarial Risk Analysis (ARA) is a structured way to model and anticipate an intelligent opponent’s choices, and using it starts with a clear framing of the decision problem. Begin by defining the defender’s objective(s), the assets at stake, the set of feasible defensive actions, and the operational constraints (budget, rules of engagement, legal limits). Simultaneously define the adversary’s possible actions and the context in which both sides will operate (timing, information availability, environmental factors). This problem framing produces the decision nodes and outcomes you will model — without a precise frame, subsequent probabilistic and game-theoretic work will be unfocused.

Next, construct models of the adversary: their preferences, capabilities, information, and likely decision rules. Use all available intelligence, historical incidents, subject-matter expertise, and structured elicitation from analysts to estimate what the opponent values (e.g., material gain, disruption, publicity) and how they rank outcomes. Represent these preferences as utility or payoff functions and estimate the adversary’s constraints (logistics, detection risk, political costs). Where direct data are lacking, use scenario-based ranges and clearly document assumptions — ARA’s strength is in making these assumptions explicit so they can be tested and updated.

Translate the problem into a probabilistic decision model that combines the defender’s actions and the adversary’s decision process. Use Bayesian methods to represent uncertainty about the adversary’s beliefs and capabilities: assign prior probability distributions to unknown parameters (e.g., adversary skill, likely attack vectors) and specify the conditional probabilities that link actions to outcomes. Then perform forward simulation or analytical expected-utility calculations: for each candidate defensive action, simulate how the adversary would respond and compute the defender’s expected utility (or loss) over the resulting outcome distribution. Comparing these expected utilities identifies which defensive options best minimize expected harm given the adversary’s modeled behavior.

Because real environments are dynamic, implement iterative updating and robustness checks. As new intelligence arrives (intercepts, pattern changes, after-action reports), use Bayesian updating to refine parameter estimates and recompute strategy rankings. Conduct sensitivity analyses to see how strategy choices change under alternative assumptions about adversary preferences or capabilities. Run structured “red team” exercises to stress-test the model: have independent analysts or an external team play the adversary, challenge key assumptions, and propose unmodeled tactics. These practices expose blind spots and produce more robust defensive plans.

Finally, integrate ARA outputs into operational decision-making and continuous monitoring. Convert model recommendations into concrete mitigation plans, metrics, and triggers (e.g., if probability of X exceeds Y, switch posture). Ensure roles and timelines are assigned for implementing countermeasures and for rapid model re-run when indicators change. Document the logic and assumptions behind chosen strategies so leaders can justify decisions under scrutiny. In short, ARA is a disciplined loop — frame → model adversary → compute expected outcomes → test and update → operationalize — that turns adaptive threats into manageable strategic choices.

Numbers That Tell the Story

The importance of risk analysis is not theoretical. According to the World Economic Forum (2024), operational disruptions now rank among the top ten global business risks. The National Retail Federation (2023) reports that theft and vandalism cost U.S. companies over $60 billion annually. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2024) recorded a 12% increase in workplace violence incidents between 2019 and 2023.

These numbers reveal a clear pattern: organizations that fail to anticipate risk inevitably pay for it — financially, operationally, and sometimes in human lives.

Balancing Strengths and Limitations

The strength of structured risk analysis lies in its transparency and repeatability. It transforms subjective intuition into a documented process that auditors, investors, and commanders can trust. It also bridges the communication gap between executives and field personnel — translating danger into data.

However, every method has limits. Smaller organizations often lack reliable statistics to support quantitative modeling. Qualitative methods depend heavily on human judgment and can be influenced by cognitive bias or political pressure. The key, therefore, is balance: choose a model that fits your resources, and refine it continuously. A simple system that evolves is better than a perfect one that gathers dust.

From Theory to the Field

To understand the real-world value of risk analysis, consider a logistics company operating a depot in a high-crime area. A review identifies several vulnerabilities: poor lighting, low fences, and inconsistent guard patrols. Over the previous year, the facility suffered three armed robberies costing roughly $100,000 each.

A quantitative analysis estimates the expected annual loss at $300,000. After implementing better lighting, surveillance, and tactical patrol schedules, the probability of a successful robbery drops by more than 80%. The residual expected loss falls to $50,000 — a reduction that pays for the improvements within months. This example embodies the essence of risk management: turning knowledge into measurable safety.

Adapting to Regional Realities

Global frameworks are valuable, but risk is always local. In Latin America, for example, high rates of armed robbery and slow emergency response times create unique challenges that differ from those in Europe or North America. Effective risk analysis must therefore include local intelligence, crime statistics, and cultural awareness.

For the ABA International doctrine, this adaptability is essential. Methodology without context is meaningless — a formula cannot replace experience. True mastery of risk analysis lies in blending universal structure with local understanding and tactical realism.

Best Practices for Armed and Corporate Security

Successful risk analysis programs share certain habits. They start simple and evolve deliberately. They document every decision for legal and strategic accountability. They integrate training, technology, and human observation. They connect metrics to performance indicators and ensure that every mitigation effort can be measured in outcomes, not intentions.

Cross-functional participation is also critical. Security cannot exist in a vacuum; operations, logistics, human resources, and finance must all contribute to the process. A single overlooked factor — such as an overworked employee or a delayed supply chain — can undermine the most sophisticated plan.

Visualization also plays a role in retention. Dashboards, heat maps, and infographics transform dense reports into actionable intelligence. They allow executives to grasp priorities instantly and empower security teams to argue for resources effectively.

The Strategic Mindset

Ultimately, risk analysis is less about paperwork and more about mindset. It teaches professionals to think in probabilities, to see vulnerabilities before they become emergencies, and to make peace with uncertainty by quantifying it.

For the armed operator, this mindset saves lives. For the manager, it saves assets and reputation. And for the organization as a whole, it fosters a culture of anticipation rather than reaction — one in which threats are expected, not surprising.

Conclusion

In a world defined by unpredictability, risk analysis is the language of control. It allows security professionals — whether in uniform, in the field, or behind a desk — to turn chaos into structure. From ISO frameworks to adversarial models, from financial loss estimation to human-factor resilience, the core mission remains the same: to predict, prepare, and prevail.

Every operation, no matter how small, deserves a systematic understanding of its own fragility. Because in security, as in life, uncertainty is inevitable — but unpreparedness is a choice.

References

- ASIS International. (2021). Enterprise Security Risk Management Survey.

- Center for Internet Security. (2022). Quantitative Risk Analysis: Importance and Implications.

- Cox, A. (2021). Structured What-If Techniques in Security Planning. Journal of Security Studies, 14(2), 122–135.

- Department of Homeland Security. (2023). Critical Infrastructure Threat Assessment Annual Report.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). (2023). Threat Landscape Report 2023.

- G4S Global Security. (2022). State of Security Operations Report.

- GAO. (2022). Quantitative Risk Management in Federal Agencies.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2018). ISO 31000: Risk Management — Guidelines.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2012). NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1: Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments.

- National Retail Federation. (2023). Retail Security Survey 2023.

- Rios, J., & Insua, D. (2020). Adversarial Risk Analysis in Security Contexts. Journal of Defense Modeling, 27(1), 88–104.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Workplace Violence Data Summary.

- World Economic Forum. (2024). Global Risk Report 2024.