Introduction

Large-scale events — from international summits and concerts to sports tournaments and political gatherings — represent some of the most complex environments for modern security management. They bring together massive crowds, high-value targets, media coverage, and unpredictable variables, all within strict time and location constraints.

Effective mega-event planning is not just about manpower or equipment; it’s about systemic coordination, intelligence-driven preparation, and risk-based decision-making.

This guide outlines the complete process — from initial assessment to post-event review — tailored for security professionals and armed operators under the ABA International doctrine.

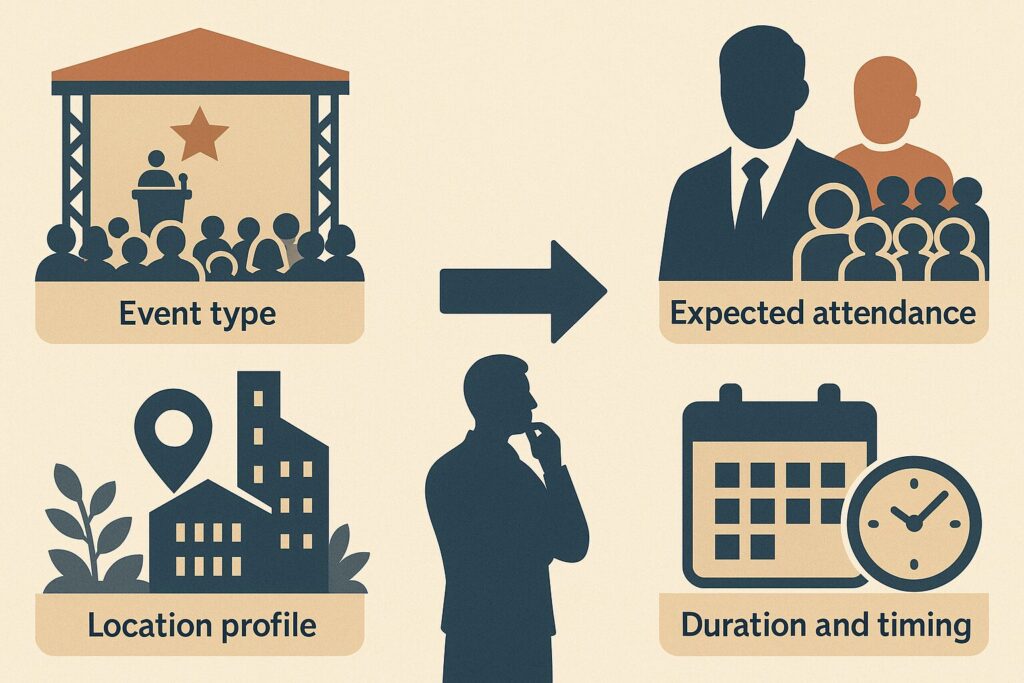

1. Defining the Operational Context

Every successful operation begins with clarity. The first step is to define the scope, objectives, and environment of the event.

- Event type: public, private, political, entertainment, or mixed.

- Expected attendance: number of participants, VIP presence, and crowd demographics.

- Location profile: open or closed venue, urban or rural, critical infrastructure nearby.

- Duration and timing: single day vs. multi-day, time of day, seasonal considerations.

Once defined, the operational context determines the command structure, legal boundaries (firearms regulations, private security laws), and the cooperation required between public authorities and private security teams.

2. Risk and Threat Assessment

At the core of mega-event planning is the risk analysis process. Following frameworks like ISO 31000 or NIST SP 800-30, the security team should:

- Identify potential threats: terrorism, crowd disorder, theft, cyberattacks, weather hazards, or insider risks.

- Evaluate vulnerabilities: structural weaknesses, surveillance blind spots, untrained staff, or communication failures.

- Determine likelihood and impact, building a risk matrix to prioritize actions.

This process must integrate intelligence gathering, including liaison with police, intelligence services, and event-specific threat monitoring. The result should be a risk register — a living document updated daily as the event approaches.

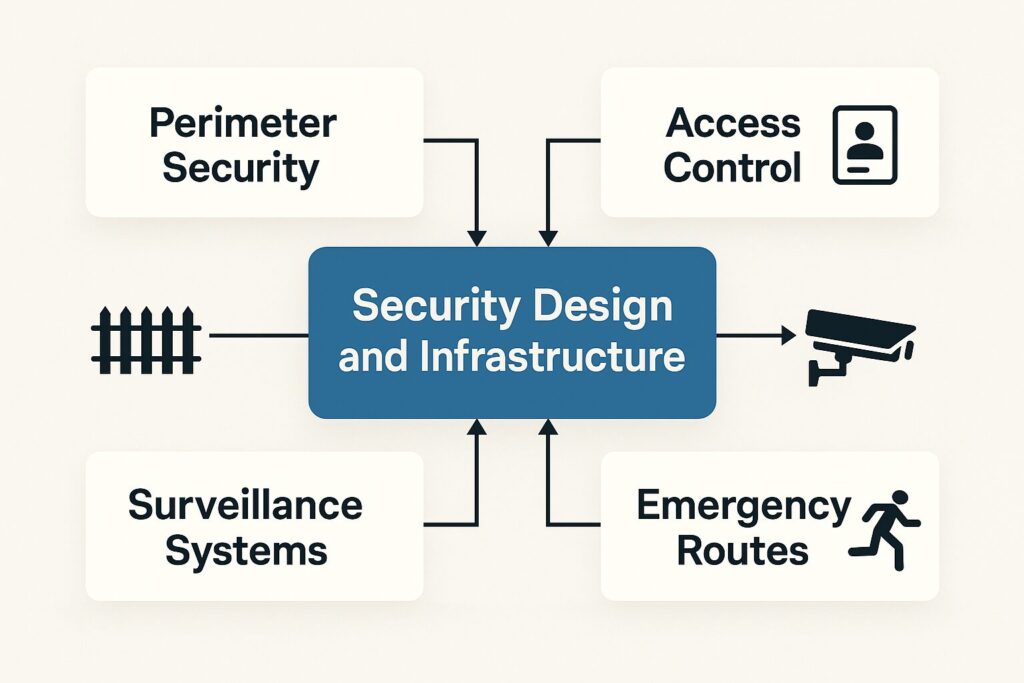

3. Security Design and Infrastructure

Once the risks are known, design the physical and procedural defenses accordingly.

- Perimeter security: fencing, barriers, controlled access points.

- Access control: badge systems, ticket validation, magnetometers, and canine units.

- Surveillance systems: CCTV, drones, and real-time monitoring centers.

- Emergency routes: clearly marked evacuation paths, medical triage zones, and muster points.

Security design must be proportional to the assessed risk and compliant with local legislation. Whenever possible, conduct rehearsals and stress tests to validate layout, flow, and reaction times.

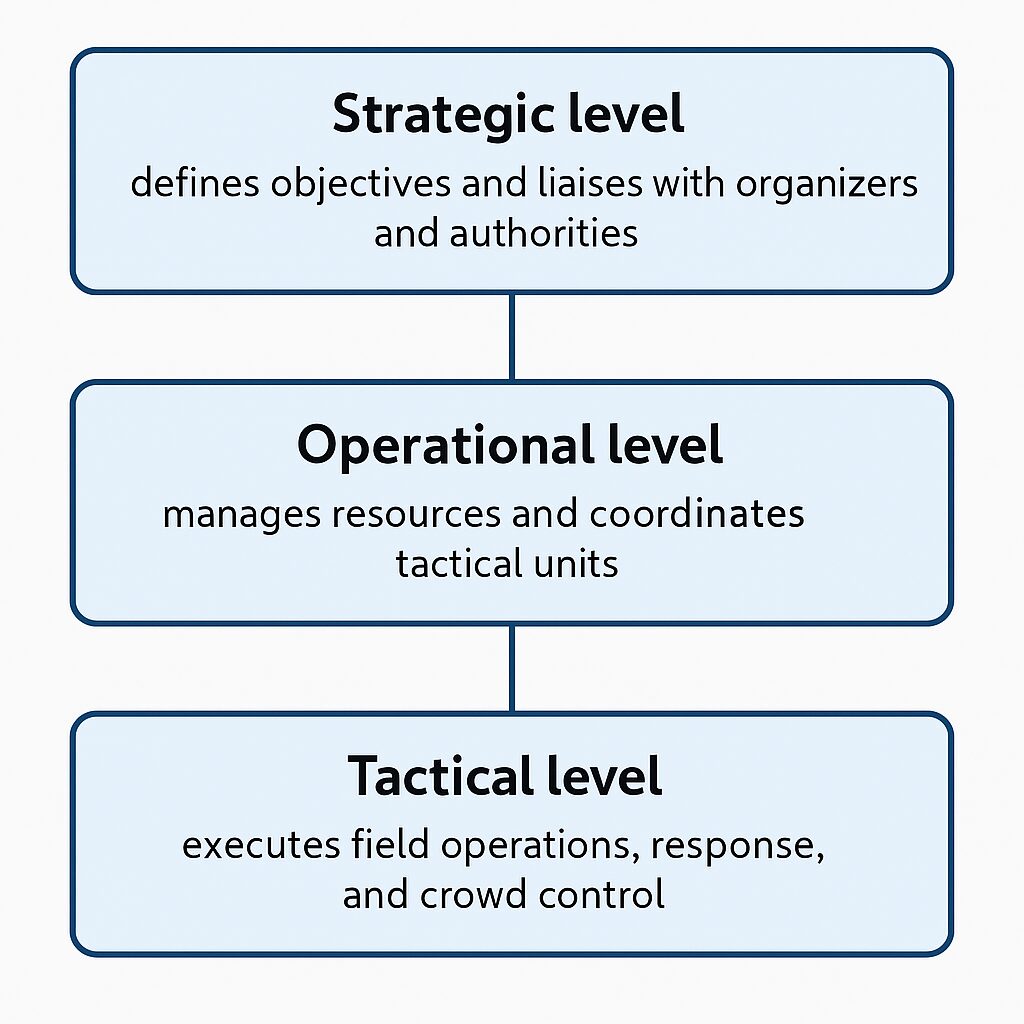

4. Coordination and Command Structure

Mega-events require multi-agency integration. Private security firms, police units, fire departments, emergency medical services, and sometimes military or intelligence support must operate within a unified structure.

The Incident Command System (ICS) model offers a proven template for establishing hierarchy and communication flow.

- Strategic level: defines objectives and liaises with organizers and authorities.

- Operational level: manages resources and coordinates tactical units.

- Tactical level: executes field operations, response, and crowd control.

Each layer must maintain redundant communication systems and clear reporting procedures. Drills should verify interoperability between radio frequencies, command posts, and digital communication platforms.

5. Personnel Management and Training

The most advanced technology cannot replace well-prepared personnel. Training should cover:

- Rules of engagement and proportionality of force.

- Crowd psychology and non-lethal intervention techniques.

- Emergency medical response and trauma care (Stop the Bleed, CPR, AED use).

- Coordination under stress and adherence to chain of command.

Armed operators must also train on weapons discipline in dense environments, deconfliction with police forces, and identification protocols to prevent blue-on-blue incidents.

6. Contingency and Crisis Management

No plan survives first contact unchanged. Therefore, planners must build layered contingency scenarios.

- Plan A: nominal operation.

- Plan B: partial disruption (VIP delay, localized protest, weather event).

- Plan C: full-scale emergency (active shooter, bomb threat, infrastructure collapse).

Each scenario must include clear triggers, decision authorities, and communication protocols for escalation and de-escalation.

Crisis management rooms should include representatives from all critical entities, equipped with live feeds, mapping systems, and backup power.

7. Communication and Public Relations

Security also depends on perception. A well-informed audience behaves more predictably.

Develop a communication strategy that:

- Keeps participants aware of entry procedures, prohibited items, and emergency routes.

- Provides real-time updates through official channels and mobile apps.

- Ensures consistency between internal (staff) and external (public) messaging.

A Public Information Officer (PIO) or media liaison should manage press interactions, ensuring the release of accurate, non-sensitive data during incidents.

8. Cyber and Technological Security

Modern mega-events rely on digital systems for registration, surveillance, and logistics.

Cybersecurity teams must secure:

- Wi-Fi networks, ticketing systems, and databases containing personal data.

- Operational technology (OT) used in lighting, power, and HVAC systems.

- CCTV and drone feeds, often connected to cloud services.

Simulated attacks — penetration testing — should be conducted weeks before the event to identify weaknesses.

Remember: in the digital era, a cyberattack can disrupt physical safety as much as an explosive device.

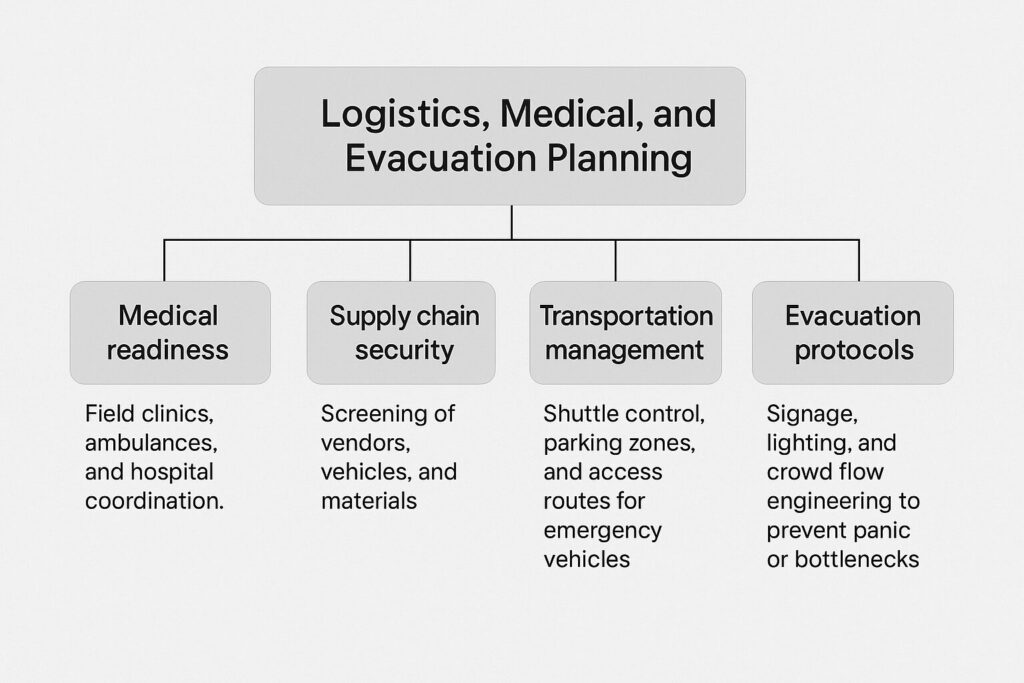

9. Logistics, Medical, and Evacuation Planning

Behind every secure event is a logistical backbone. This includes:

- Medical readiness: field clinics, ambulances, and hospital coordination.

- Supply chain security: screening of vendors, vehicles, and materials.

- Transportation management: shuttle control, parking zones, and access routes for emergency vehicles.

- Evacuation protocols: signage, lighting, and crowd flow engineering to prevent panic or bottlenecks.

Every component must be time-tested through simulation exercises.

10. Post-Event Review and Lessons Learned

The event may end, but the process continues. After-action reviews (AAR) identify what worked, what failed, and what must change.

Gather data on:

- Incident reports, equipment failures, and response times.

- Communication logs and decision points.

- Feedback from teams and external partners.

These findings should feed into a continuous improvement cycle, strengthening institutional knowledge for future operations.

Conclusion

Planning a mega-event is an art of foresight, coordination, and adaptability. It demands the same discipline as a military operation, but with the flexibility of a public service. By applying structured risk assessment, interagency coordination, and constant training, security professionals ensure not just the safety of participants, but also the credibility of the institutions behind the event.

At ABA International, we believe that security planning is not reactive — it is predictive. Every decision, every layer, and every protocol must anticipate, not chase, the threat. Because in the world of mega-events, success is defined not by what happened, but by everything that didn’t.