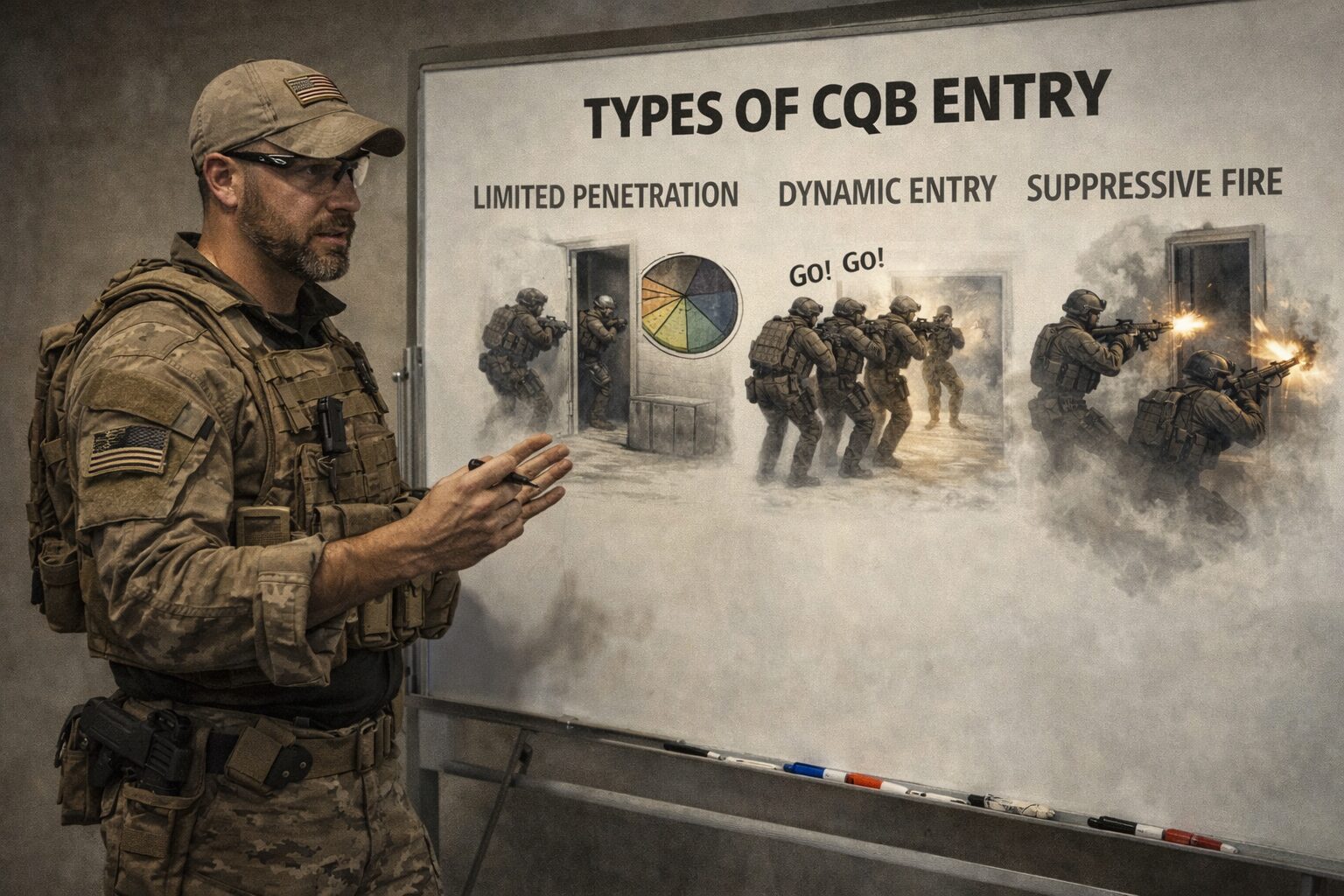

Close Quarters Battle (CQB) refers to combat conducted at very short distances, typically inside buildings, confined spaces, or dense urban environments. At these ranges, time, space, and information are extremely limited, and the margin for error is minimal. Over time, three broad operational approaches to CQB have emerged, each driven by mission objectives, threat profile, rules of engagement, and force composition: Limited Penetration, Dynamic, and Suppressive CQB.

1. Limited Penetration CQB

Definition

Limited Penetration Close Quarters Battle (LP-CQB) is a deliberate room-clearing methodology in which operators minimize physical entry into a space while progressively clearing sectors of fire from outside or at the threshold. The objective is to gain visual and ballistic dominance incrementally while reducing exposure to unknown threats.

Core Principles

1. Incremental Angle Clearance

Operators clear the room by progressively exposing only small portions of their body while visually and ballistically dominating new angles (“slicing the pie”). Each movement clears a defined sector before advancing.

2. Minimal Exposure Doctrine

At no point is the operator fully committed to the room unless tactically justified. The body remains bladed, weapon oriented, and exposure is limited to what is strictly necessary to clear the next slice.

3. Information Before Commitment

LP-CQB prioritizes information acquisition over speed. Visual confirmation, shadow reading, reflection use, and auditory cues guide decisions before entry.

Execution Framework

Positioning

- Weapon remains indexed on uncleared space

- Feet remain outside or just at the threshold

- Strong-side and support-side slicing depending on door hinge orientation

Movement

- Lateral micro-steps, never forward surges

- Each step corresponds to a newly cleared angle

- Movement pauses at every slice to confirm dominance

Fire Control

- No speculative fire

- Engagement occurs only once positive identification and dominance are achieved

- Backstop awareness is critical due to shallow angles

Advantages

- Maximizes survivability against unknown threats

- Reduces exposure to ambush, cross-fires, and immediate contact

- Ideal for single-operator CQB or small elements

- Superior for reconnaissance, warrant service, and hostage-adjacent environments

Limitations

- Slower than Dynamic CQB

- Less effective against barricaded or fortified adversaries

- Requires high discipline, patience, and visual processing skills

- Can be defeated if overused against mobile threats

Typical Use Cases

Threshold evaluation before escalation to Dynamic or Suppressive CQB

Law enforcement entries with limited intelligence

Civilian defensive CQB inside residential structures

Solo or two-man clearing

2. Dynamic CQB

Dynamic Entry is a close-quarters battle methodology centered on speed, aggression, and immediate domination of space. Its primary objective is to overwhelm the adversary’s cognitive and physical capacity to react by combining rapid movement, synchronized team actions, and decisive violence of action. Rather than cautiously managing uncertainty, Dynamic Entry seeks to collapse the decision-making cycle of the threat as early as possible in the engagement.

This approach is characterized by an explosive breach or threshold crossing, followed by immediate penetration into the room or confined space. Operators move decisively past fatal funnels, aggressively claiming interior positions of advantage. The emphasis is not merely on entering the space, but on owning it instantly, denying the adversary time, angles, and initiative.

Dynamic Entry relies heavily on coordination, rehearsed roles, and disciplined movement patterns. Each team member is assigned a clearly defined sector of responsibility, ensuring rapid angle coverage and minimizing overlap or hesitation. Speed is not pursued recklessly; rather, it is applied deliberately as a tactical tool to create shock, confusion, and disorientation in hostile actors.

This methodology assumes a high level of training, physical conditioning, and command-and-control. Errors during Dynamic Entry—such as poor spacing, target fixation, or breakdowns in communication—carry severe consequences due to the compressed timelines involved. For this reason, it is most appropriate for units capable of sustaining precise execution under extreme stress.

Dynamic Entry CQB is particularly effective in scenarios where surprise can be achieved, where the presence of hostile actors is highly probable, and where hesitation would increase overall risk to the team or to non-combatants. When properly executed, it shifts the engagement decisively in favor of the entry team by seizing initiative and dictating the tempo of the fight from the first moment of contact.

In summary, Dynamic Entry is not merely a fast way to clear a room; it is a doctrine of controlled aggression, designed to dominate confined environments through speed, synchronization, and immediate tactical supremacy.

3. Suppressive CQB

Suppressive Close Quarters Battle (Suppressive CQB) is an approach centered on fire superiority and control of enemy behavior rather than speed or stealth. Its primary objective is to deny the adversary freedom of movement, observation, and effective decision-making through the deliberate application of suppressive effects, enabling friendly forces to maneuver, isolate, or systematically dominate confined spaces.

Unlike Dynamic Entry, which seeks immediate shock and spatial domination, Suppressive CQB accepts a more deliberate tempo in exchange for tactical control and reduced exposure during movement. Fire is employed as a shaping tool, fixing hostile elements in place, disrupting their ability to react coherently, and preventing repositioning within the structure.

This methodology is typically executed through coordinated fire and maneuver at close range. One element applies controlled suppressive fire—direct or indirect—while another element advances, repositions, or clears designated sectors. Suppression is not indiscriminate; it is applied purposefully to known or suspected enemy positions, choke points, and lines of movement, with constant attention to backstops and structural penetration risks.

Suppressive CQB is particularly suited to high-threat environments, including military urban operations, complex structures with multiple adversaries, or scenarios where the enemy possesses comparable firepower and intent. In such contexts, attempting rapid dynamic entry may result in unacceptable casualties. Suppression creates the conditions necessary for safe movement and progressive domination of the space.

This approach demands robust command and control, ammunition discipline, and a clear understanding of geometry within confined environments. Poorly managed suppression can degrade situational awareness, increase the risk of fratricide, or unnecessarily damage critical infrastructure. As such, suppressive CQB is most effective when executed by well-trained units operating under clearly defined rules of engagement.

In essence, Suppressive CQB is a doctrine of control through pressure. Rather than racing to seize space, it systematically constrains the enemy’s options until maneuver, clearance, or neutralization can occur under favorable conditions. When applied correctly, it transforms confined environments from unpredictable threats into manageable tactical problem sets.

Conclusion

These three CQB approaches—Limited Penetration, Dynamic, and Suppressive—are not mutually exclusive doctrines but tools within a tactical spectrum. A competent unit must understand not only how each method works, but when and why to apply it. The ability to transition between them, or blend elements as the situation evolves, is what ultimately defines effectiveness in close quarters combat.